|

Alaska

Native Land Claims

|

|

|

Unit

4 - The

Land Claims Struggle

|

|

|

Chapter

19 - Improved Prospects

|

|

Chapter 19

Improved Prospects

Congressional hearings on proposed claims legislation had been held in 1969, but no bill had emerged from either committee. Natives, however, had won a continuation of the land freeze, and the oil lease sale had raised the stakes of the settlement effort. Publicity efforts of the AFN and the Association on American Indian Affairs had resulted in support from major national newspapers and publications for Native proposals for congressional settlement.

In addition, the AFN was now represented by a former Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Arthur J. Goldberg. His association with the AFN enhanced its national image; his distinguished reputation and prestige was to emphasize the rightness of the Native cause. Before the year ended he was joined by other counsel of national stature, including Ramsey Clark, a former U.S. Attorney General.

By early 1970 the Senate seemed prepared to move quickly on the land claims legislation. But the AFN began to worry that Senator Henry Jackson's bill with its meager land provisions would pass. And Natives were angry at opposition to the AFN land bill from Governor Keith Miller, who had succeeded to that office upon Hickel's departure for the cabinet post. Despite rising protests from Native leaders over the State's abandonment of the Task Force recommendations, Miller continued to oppose a 40 million-acre settlement and the mineral revenue-sharing provision.

The impatience and frustration of Native leaders was dramatically emphasized in a speech AFN president Emil Notti delivered in Senator Jackson's home state of Washington in February of 1970. Notti declared that, if Congress passed a bill which did not provide a land settlement that was fair, Natives should petition for a separate nation in western Alaska. He said that an inadequate settlement bill would make the Alaska Native people as homeless as the Jewish people were before the nation of Israel was created for them. Notti said that a new nation in western Alaska could be open to American Indians as well as Alaska Natives. He said, "I will only say that it happened in Israel for a persecuted people. Why not here for a people who have lost a whole continent?" His militant stance was promptly endorsed by other Native leaders.

Objections to bill. In April, Senator Jackson's committee confirmed the fears of Native leaders by recommending to the Senate the adoption of Jackson's claims settlement bill.

While the bill could be applauded for the size of the total compensation awarded, one billion dollars, the revenue-sharing authorized was only for a limited number of years. But there were even more serious objections made by AFN.

The cause for strongest objection by Natives was the bill's land provisions. Land to which Natives would obtain formal title would be only slightly more than 10 million acres. One leader's reaction: "A real stunner!"

A second problem was that, instead of the 12 regional corporations sought by the AFN, only one — for the Arctic Slope — was authorized. Two statewide corporations, one for social services and another for investments. were also authorized.

Yet another major problem was what Natives called a "termination" clause. Within five years of enactment, the educational and social programs of the Bureau of Indian Affairs would cease and they would be assumed — maybe — by the State of Alaska.

Senator Ted Stevens, who had been appointed to his seat in 1968 upon the death of Senator E.L. Bartlett, urged acceptance of the Jackson bill. "I think this bill is a fair bill," he told the Tlingit-Haida Central Council. "It gives you more control and self-determination than any such bill in history."

|

| U.S. Senator Mike Gravel, Governor William A. Egan, U.S. Senator Ted Stevens, and U.S. Representative Nick Begich |

While Stevens may have been right in his comparison, Alaska's Eskimos, Indians, and Aleuts had declared they wanted land adequate to protect their ancient ways of life. Before the Senate Committee's bill was officially reported to the Senate, an AFN delegation was on its way to Washington.

When the Jackson bill reached the floor of the Senate for action in July, Senators sympathetic to the AFN position sought to amend it, but they were unsuccessful. The bill was adopted by a vote of 76-8.

It was now necessary for the AFN to look to the House of Representatives to adopt a bill more favorable to the interest of Alaska Natives.

Other gains. The setback suffered by AFN in the Senate was offset in some measure by other developments of 1970 which were favorable.

One was the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court which had the effect of supporting the position of Natives regarding the land freeze. By declining to review a lower court decision, the Supreme Court rejected the State's appeal that it should be free to proceed with land selections.

A second important development was AFN's success in obtaining a loan of $225,000 from the Yakima Indian Nation of the state of Washington. Until this loan was obtained, AFN had been trying to stretch an earlier $100,000 loan from Tyonek to cover its expenses as well as depending upon voluntary donations of AFN board members and church organizations.

In September of 1970, Natives won their first legislative battle of the year. The House Subcommittee on Indian Affairs agreed informally to a provision that would have granted Natives title to 40 million acres of land. Since the subcommittee would fail to report its recommendations in 1970, there was to be no further action in the House during the year. The subcommittee agreement, however, was the first taste of victory for Natives regarding the extent of land settlement.

The decision of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) to give unqualified support to the AFN and to assist in obtaining Congressional action provided a significant source of national political support. The NCAI was the largest, as well as the oldest, national organization of Indians.

Additionally, the prospects for a land settlement acceptable to AFN were improved as a result of the 1970 elections. Former governor William A. Egan, who had shown himself willing to work with the AFN, defeated the incumbent governor, Keith Miller. State Senator Nick Begich, who had said 10 million acres was an inadequate settlement, was elected as Alaska's congressman.

Changes to AFN proposal. The upsetting withdrawal of the Arctic Slope Native Association that took place during the October meeting was also to be resolved before the year ended. The break had come about because of Arctic Slope leadership opposition to the AFN plan of distributing benefits. Distribution on the basis of a region's population as urged by a majority of AFN members, was characterized by Arctic Slope executive director Charles Edwardsen, Jr., as "welfare legislation," not a land claims settlement. Edwardsen insisted that the settlement be divided on the basis of a region's historic land area, explaining that the AFN's position would "not provide for a fair exchange between what is being taken from us and what we would receive in exchange."

|

| New AFN president Donald Wright (center) with Philip Guy, vice-president, and Frances Degnan, secretary |

Return of the Arctic Slope Native Association to AFN was achieved through a compromise in December at a board of directors meeting. This meeting was presided over by Donald Wright, who had been elected to the presidency in October following Emil Notti's decision not to seek a fourth term.

The new AFN proposal developed at the meeting kept the concept of 12 regions, initial compensation of $500 million, and the two-percent share in future revenues from public lands, but raised the land provision to 60 million acres. The proposal also accepted the Arctic Slope argument that the regions with the largest land area should receive the most land and money, not the regions with the largest population.

|

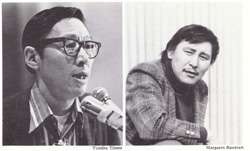

| Arctic Slope President, Joe Upicksoun, and Executive Director, Charles "Etok" Edwardsen, Jr. |

The president of the Arctic Slope Native Association, Joseph Upicksoun, had added to the justification given earlier by Edwardsen for his group's position. He told leaders of other regions:

We realize each of you has pride in his own land. By an accident of nature, right now the eyes of the nation and the world are centered on the North Slope . . .

Without intending to belittle your land, the real reason for the entire settlement is the oil, which by accident is on our land, not yours.

Under the proposal, apart from an initial $8 million payment to each region, the $500 million and whatever land was obtained in the settlement would be distributed on the basis of lands lost. Money from mineral developments, however, would be shared among the regions. Arctic Slope, for instance, would retain half of the revenues it received from mineral development and distribute the remainder to other regions on a population basis.

These two provisions, the "land loss" formula and the revenue-sharing proposal, were the foundation for a settlement acceptable to Native regions having mineral potential and those without, and those having large populations and those only lightly populated. In modified form, these two provisions would later be reflected in the legislation adopted.

| Alaska Native Land Claims Copyright 1976, 1978 by the Alaska Native Foundation |