|

Alaska

Native Land Claims

|

|

|

Unit

3 - Alaska Natives and Their Lands

|

|

|

Chapter

13 - Renewed Promise

|

|

Chapter 13

Renewed Promise

|

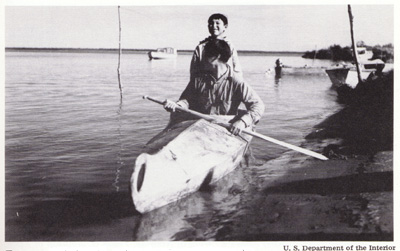

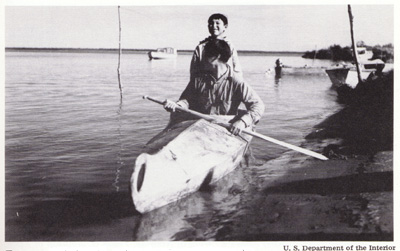

| Two youths in kayak on the Kuskokwim River, 1939 |

Even with citizenship it would be more than a generation before Natives acquired enough political importance to significantly affect the legislative process. In the meantime — in the 1930's, 1940's, and 1950's — there was renewed promise that Native rights to land would be protected or, if not, that these rights would be purchased. This promise was suggested in three ways — the Indian Reorganization Act, the Alaska Statehood Act, and the Tlingit-Haida court decision.

Reservations. Preserving large areas for the use and occupancy of Alaska Natives became a possibility in 1936. This came about by Congressional action extending the Indian Reorganization Act to Alaska.

The Indian Reorganization Act (also called the Wheeler-Howard Act) was enacted in 1934 to curb the loss of Indian lands and to restore lands already lost under the Dawes Act of 1887. Under its provisions, the U.S. Department of the Interior could establish reservations for Eskimos and Indians in Alaska. Such reservations, it will be recalled, would not mean title for the people living on them. Title would be held in "trust" for them by the Department.

|

| Fish drying racks and food storage cache, Unalakleet, 1939 |

The act became the focus of wide controversy. Both Natives and whites raised objections to it. Non-Natives were fearful that land would be locked up — preventing the development of resources and the growth of the territory's economy. Natives — especially those who were familiar with reservations elsewhere in America — feared that they might be confined to small areas with limited resources.

Despite the controversy, seven reservations were established between 1941 and 1946. The largest, which included the villages of Venetie, Arctic Village, Kachik, and Christian Village, was 1,408,000 acres; the smallest — Unalakleet — was 870 acres. The others were established at Akutan, Diomede, Hydaburg, Karluk, and Wales.

A court held later than the Hydaburg reservation had not been legally established. Three other villages where reservations were proposed voted them down.

One reason for the creation of reservations was the continuing increase in the non-Native population of the territory. Their numbers reached about 40,000 in 1939 and, with the building of the defense systems for World War II, had mushroomed by the mid-1940's. In requesting the reservations, the Secretary of the Interior explained the threat:

The large influx of population into Alaska as a result of war activities, and the growing encroachment of the whites upon the land and resources of the Indians and Eskimos have served to emphasize the most serious problem confronting the Natives — the protection of their ancestral hunting, trapping, and fishing bases.

By 1950, 80 additional villages had submitted petitions to the Secretary requesting reservations of 100 million acres. What happened in response to their petitions? Writing much later, in Alaska Natives and the Land, Esther Wunnicke reported succinctly: "No action was taken." The likely reason for inaction was that public opinion of the 1950's seemed opposed to reservations and what they represented: racial segregation and discrimination.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act only a few villages had obtained protection against encroachments by others.

Political gains. Following William Paul's example of 1924, other Natives filed for legislative seats and some won. In 1944, Frank Peratrovich of Klawock and Andrew Hope of Sitka were elected to the Territorial House of Representatives; in 1946 Frank G. Johnson of Kake was elected to the House and Peratrovich to the Senate. In 1948, Peratrovich became Senate president. In the same year, the first Eskimos were elected to the Territorial legislature; they were Percy Ipalook of Wales and William E. Beltz of Nome. Then in 1950, Frank Degnan of Unalakleet and James K. Wells of Noorvik won House seats.

|

THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION AND NATIVE LAND RIGHTS Rights of Natives to land were the subject of an extended debate at the 1955 Alaska Constitutional Convention in Fairbanks. The debate was triggered by a proposal made by Col. M.R. "Muktuk" Marston of Anchorage, who during World War II had organized the Eskimo Scouts of the Alaska Territorial Guard. Marston's proposal was that Eskimos, Indians, and Aleuts be granted title to land parcels of 160 acres they were using and occupying. It also included a provision that would leave open the larger issue of Native claims. Marston told the Convention that the Native Allotment Act was of no help to most Natives. He explained that he had tried for three years to help George Lockwood of Unalakleet protect his land, but that he had failed. Pointing to a map, he said:

Although a disclaimer regarding Native lands was adopted, Marston's proposal was rejected. Summarizing the five-hour debate in his book, Alaska's Constitutional Convention, Victor Fischer wrote:

Fischer explained that many revisions were made — including "Alaskans" in place of "Eskimos, Indians, and Aleuts" — that led to confusion about the issues. "Thus," he wrote, "the proposal for granting land rights to Alaska Natives went down to defeat without ever coming to a direct vote on the basic issues involved." |

|

|

||||

|

In the legislative session which began in 1952, Natives held seven seats. Although this was a substantial gain from the time Paul was the only Native legislator, it was still but a small minority of the total membership.

Statehood. When the Organic Act of 1884 had been enacted, it appeared to promise protection for lands used and occupied by Natives. It had failed in that promise.With the Statehood Act of 1958, the promise was renewed. In the act, the new State and its people disclaimed all right or title to lands "the right or title to which may be held by Eskimos, Indians, or Aleuts" or held in trust for them.

The act, however, did not define the "right or title" which Natives might have. This was left to future action by the Congress or the courts.

Alaska was admitted as a state on January 3, 1959. By 1961, the promise of the disclaimer was to be overshadowed by another provision of the act. This provision — in part the subject of the next chapter — was the grant of about 103 million acres of land to the new state.

|

| At Gambell, 1948. Lester Nopawhotak |

Tlingit-Haida decision. While the promise of protection for land rights was again to be unfulfilled, 1959 brought promise of another kind: payment to Natives for lands which were theirs, but taken by others. This was the decision of the Court of Claims in the Tlingit-Haida case.

The court action had its beginnings in 1929 at an Alaska Native Brotherhood meeting in Haines. Out of discussions begun there, the Congress passed a law in 1935 allowing Tlingits and Haidas to sue the United States for the loss of their land to others. By this time, nearly all of southeastern Alaska was the Tongass National Forest, Glacier Bay National Monument, or set aside as a reservation for Tsimshian Indians from Canada.

In their suit, long delayed by attorney problems and by the possibility of obtaining reservations, Tlingits and Haidas had asserted that the United States had taken land which was theirs by Indian title. After reviewing the evidence and the arguments of opposing attorneys, the court issued its findings of fact (96 pages) and its decision (26 pages). In conclusion — in the words of the court — the Tlingits and Haidas have established their use and occupancy, i.e., Indian title, to the lands and waters of virtually all of southeastern Alaska. Furthermore, the court concluded:

In deciding in favor of Tlingits and Haidas the Court said they were entitled to compensation for "all usable and accessible land which they used and occupied." It was to be another nine years before the Court placed a value upon the 16 million acres taken by the government.

| Alaska Native Land Claims Copyright 1976, 1978 by the Alaska Native Foundation |