|

Alaska

Native Land Claims

|

|

|

Unit

5

- The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act: An Introduction

|

|

|

Chapter

21 - Land and Money

|

|

|

THE ALASKA NATIVE CLAIMS SETTLEMENT ACT: AN INTRODUCTION

"The Settlement Act is a complex settlement of a complex situation. Some of its provisions are susceptible to differing interpretations, the more so because there are three parties-at-interest: The Natives, the State of Alaska, and the Federal government, which still has vast riches and vast responsibilities in Alaska. Many problems have arisen already and many more will arise in the implementation of the law.

Enactment required goodwill and broad statesmanship. Fulfillment of the spirit and letter of this historic legislation will require the same great qualities.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act is monumental legislation of which all Americans, Native and non-Native, can be proud."

Steward French, "Alaska Native Claims

Settlement Act,"

The Arctic Institute of North America,

August 1972

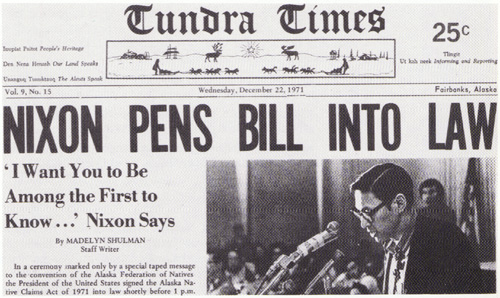

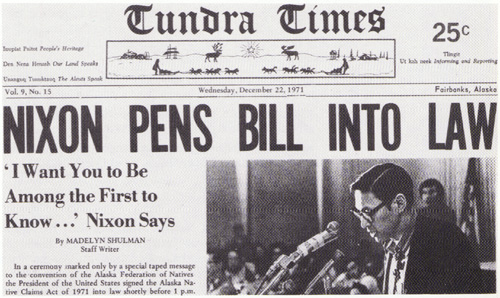

When the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was signed into law on December 18, 1971, it was hailed by the Tundra Times as "the beginning of a great era for the Native people of Alaska."

That the Congress held a similar view is suggested by a statement of policy which was made a part of the act. In adopting the act, the Congress had declared, in part, that the settlement should be accomplished:

Under the act, Alaska Natives would receive fee simple title to 40 million acres of land. Native claims based on aboriginal title to any additional lands in Alaska were extinguished. Existing reserves, except for Annette Island, were revoked. The Native Allotment Act, which had also allowed trust status, was revoked. Compensation for claims extinguished was set at $962.5 million, which would be paid over a number of years.

All United States citizens with one-fourth or more Alaska Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut blood who were living when the settlement bill was enacted were qualified to participate, unless they were members of the Annette Island Reserve community of Metlakatla. (As noted earlier, Tsimshian Indians of this community had been granted a reserve by Congress in 1891, following their emigration from Canada.)

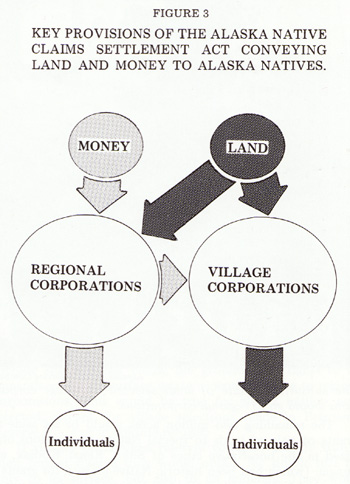

Benefits under the settlement act would accrue to Natives not through clans, families, or other traditional groupings, but, instead, through the modern form of business organization called a corporation. All eligible Natives were to become stockholders part owners of such corporations.

The first step for a Native to take to become a stockholder would be to enroll to register his name, his community and region of permanent residence, and to prove that he was an Eskimo, Indian, or Aleut as defined in the act. Based upon the region which he considered his permanent home, he would be enrolled and become a holder of 100 shares of stock in one of the 12 (or perhaps 13) regional corporations to be created under the act.

The act provided that no rights or obligations of Natives as citizens, nor rights or obligations of the government towards Natives as citizens, would be replaced or diminished. It called, however, for a study of federal programs affecting Natives to see whether changes of any kind should be considered. Within three years, the Secretary of the Interior was to deliver his recommendations to Congress regarding the future operation and management of these programs.

The act also authorized the Secretary of the Interior to withdraw up to 80 million acres of land in Alaska for study to determine if these lands should be added to existing national parks or forests, wildlife refuges, or wild and scenic river systems. Following the study, the Secretary would make recommendations regarding the lands to Congress.

A 10-member Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission was to be established to make recommendations concerning use or disposition of lands in Alaska. Broadly told, the Commission's role would be one of developing recommendations that would take into account the interests of various groups of people, such as Natives and other residents of Alaska, and the interests of the people of the nation as a whole.

Chapter 21

Land and Money

In terms of the land and money settlement, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was clearly an historic event. With extinguishment of their aboriginal claims, Alaska Natives were to obtain fee simple title to more land than was held in trust for all other American Indians. And compensation for lands given up was nearly four times the amount all Indian tribes had won from the Indian Claims Commission over its 25-year lifetime.

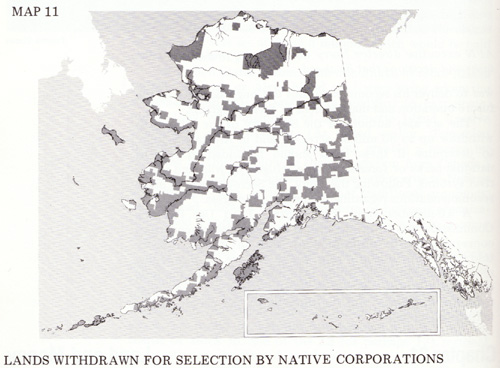

Land. To assure that 40 million acres would be available for selection by Natives, the Secretary of the Interior was to set aside land around villages and elsewhere before the land freeze was lifted. Such withdrawal would protect these lands over the three-year period in which village corporations could make their selections and the four-year period in which regional corporations could make their selections. Land already in private ownership could not be chosen. Land in national parks or lands set aside for national defense purposes could not be chosen either, except for the surface of lands in Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4, in northwest Alaska.

Of the 40-million-acre settlement, 22 million acres were earmarked for selection by villages. As with the money distribution, the number of acres to which a village was entitled was to be determined by enrollment. With some exceptions noted below, entitlements would be determined as follows:

|

Enrollment |

Entitlements |

|

25 through 99 |

3 townships (69,120 acres) |

|

100 through 199 |

4 townships (92,160 acres) |

|

200 through 399 |

5 townships (115,200 acres) |

|

400 through 599 |

4 townships (138,240 acres) |

|

600 or more |

4 townships (161,280 acres) |

The village corporations would own only the surface estate to lands they selected. Their ownership would not include the minerals below the ground. The rights to the minerals the subsurface estate would belong to regional corporations. This would be true for all 22 million acres selected, except for village selections made in Petroleum Reserve No. 4 or in wildlife refuges.

If villages on revoked reserves voted to acquire title to their former reserve they would obtain fee simple title not only to its surface, but also to its minerals. They would forego, however, other benefits under the act.

Once villages obtained their lands, they would transfer some tracts to individuals Native or non-Native, some to organizations, and some to municipal, state, or federal governments, and retain the remainder.

Sixteen million acres of land would be selected by regional corporations on the basis of land area within their regions, rather than population. Under a complicated land-loss formula, these lands would be chosen by whichever of 11 regional corporations had small enrollments but large areas within their boundaries. Owing to the earlier Tlingit-Haida settlement, the southeastern region would not be among the corporations eligible for this provision.

The remaining two million acres would be set aside for grants of title of lands to special Native corporations organized in the non-Native cities of Sitka, Kenai, Kodiak, and Juneau (which had been historic Native places); for grants to groups of Natives or to individual Natives residing away from villages; for Native allotments which were filed for before the passage of the act; and for cemeteries and historic sites.

Payments from the Alaska Native Fund would be made only to regional corporations. They, in turn, would retain part of the funds and pay out part to individual Natives and village corporations.

The amount of money each regional corporation would receive was to be based upon its proportion of enrolled Natives to the total number enrolled. During the first five years, at least 10 percent of the claims money and other income received by a regional corporation was to be distributed directly to individuals its stockholders and at least 45 percent of such money was to be distributed to village corporations within its boundaries.

The amount received by each village corporation was to be based upon its proportion of stockholders to the total number of stockholders in the region. Natives enrolled to regional corporations but not to villages would receive their proportionate share directly, which meant that their payments would be larger than if they were also enrolled to villages. They would not be granted land by village corporations, however, or otherwise benefit from activities these corporations carry out.

| Alaska Native Land Claims Copyright 1976, 1978 by the Alaska Native Foundation |