Terrestrial Animals

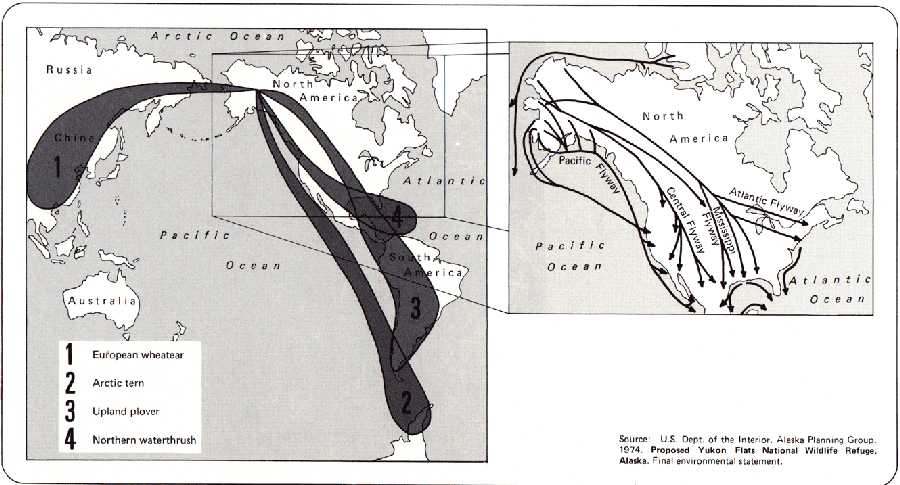

Each animal occupies a habitat niche that meets all its requirements—a limited area in some cases and a wide area in others. Migrating birds, for example, take advantage of the abundant sunlight and rapid growth of food plants for nesting during the short subarctic summer, but retreat in winter to milder climates. Their habitat requirements may span two continents (Figure 165).

Figure 165. Waterfowl Migration Routes from Alaska

Some animals modify their habitats. Slow-growing lichens on caribou range require many years to regrow after repeated grazing. Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), introduced in 1944 on St. Matthew Island where there were no predators, had increased and so altered their range by the mid-1960s that they could no longer survive. Other species increase the productivity of their communities. A myriad of soil invertebrates—protozoa, various worms, primitive insects, and mites—speed the breakdown of plant and animal litter, releasing nutrients for new plant growth.

The Yukon Region encompasses a wide variety of animal habitats. Tundra-covered St. Matthew, Pinnacle, and Hall Islands in the Bering Sea, support a limited number of terrestrial species, mainly seabirds. The broad, lake-strewn, marshy tundra of the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta supports an abundance of animals of various species and is one of the largest single units of waterbird habitat in Alaska (Figure 165). The sparsely timbered marsh- and lake-dotted lower Yukon-Innoko-Koyukuk drainages support an abundance of less maritime species. The greatest productivity of interior habitats, particularly for birds, is centered on the broad valley systems which King and Lensink (1971) describe as "solar basins"—areas with rich alluvial soils sheltered from storms, heavy summer rains, and cloud cover by surrounding mountain ranges. Such basins of the upper Yukon, Tanana, and Porcupine Rivers are some of the most productive wildlife habitats in the region. The Yukon Flats, nearly 11,000 square miles (28,490 km2), is the largest of the highly productive habitats in Alaska for bird life and supports an abundance of mammals of various species. The Minto Flats and Tetlin Lake are also centers of high production of water-oriented animals. Scrubby timber, brush, marsh, and muskeg are interspersed throughout these interior valleys that also support upland species.

Less productive are the rolling hills and mountains that surround these broad valleys. Many are covered with unbroken spruce forest and support few animals. Red squirrel and pine marten, which can meet all their habitat requirements in this single type, are exceptions. The alpine tundra of the higher mountains of the Brooks Range, Alaska Range, and White Mountains, however, supports a normal complement of animal species.

Mammals

St. Matthew, Hall, and Pinnacle Islands are the least-occupied terrestrial mammal habitats of the region. Meadow voles (Microtus abbreviatus) and Arctic foxes are the sole mammalian representatives. Recent overflights by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service failed to reveal survivors of the herd of introduced reindeer.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim delta (Figure 167), an important habitat for waterbirds, supports most Alaskan species found in salt marsh or on wet or moist tundra, but not in major concentrations. In general, their abundance decreases toward the coast where brush or tree cover is almost absent. Exceptions are the Arctic fox, which is a part-time inhabitant of sea ice, and the mink, which dwells in marshlands and water areas and attains its largest size on the delta.

The lower Yukon-Innoko-Koyukuk drainages support higher mammal populations. The broad valleys, covered with mixed spruce-hardwood and muskeg-bog vegetation, and the river islands and bars, covered with young willows, provide year-round range for moose. This intermixture of types which occurs there and elsewhere in the Yukon Region is favorable for moose as well as numerous other woodland mammals.

Moose prefer the upriver areas where tundra gives way to timber. Caribou of the Arctic herd, which numbered nearly 250,000 animals in a census conducted in 1971 by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, winter throughout the upper Koyukuk drainage about as far south as Hughes and Hog River. The small Beaver herd ranges in the lnnoko drainage, and caribou from other less well-defined herds also range into the area occasionally. Caribou use a wide variety of habitats, but the best winter range is in sparse upland spruce timber where they can paw through the snow cover to the lichens beneath (Pruitt 1960). Some windblown alpine slopes also provide good forage. Other suitable winter range probably consists mainly of sedges. The grizzly bears of the Yukon Region, which do not attain the size of their counterparts on the coast, tend to favor open slopes and mountainous areas along the lower Yukon-Innoko-Koyukuk area and elsewhere throughout the region. Black bears range throughout forested valleys, showing a preference for open mixed forests. They do not commonly inhabit moist or wet tundra, but they may traverse alpine tundra as they search for roots and berries. Dall sheep live in the Brooks Range in the headwaters of the Koyukuk drainage as well as in similar habitats of the Brooks and Alaska Ranges farther east. They occupy much of the alpine tundra in summer, but stay on slopes blown clear of snow in winter. Wolves and wolverines forage year-round in various habitats from the main river channels to high mountain ridges. Other terrestrial mammals occur where they find suitable habitat.

|

|

The upper reaches of the Yukon, Tanana, and Porcupine Rivers support similar terrestrial mammal populations, probably in greater abundance than downstream habitats. This varies locally depending on habitat conditions which may change because of fire or hunting pressure. The effects of such other factors as predator populations and climate are not well understood.

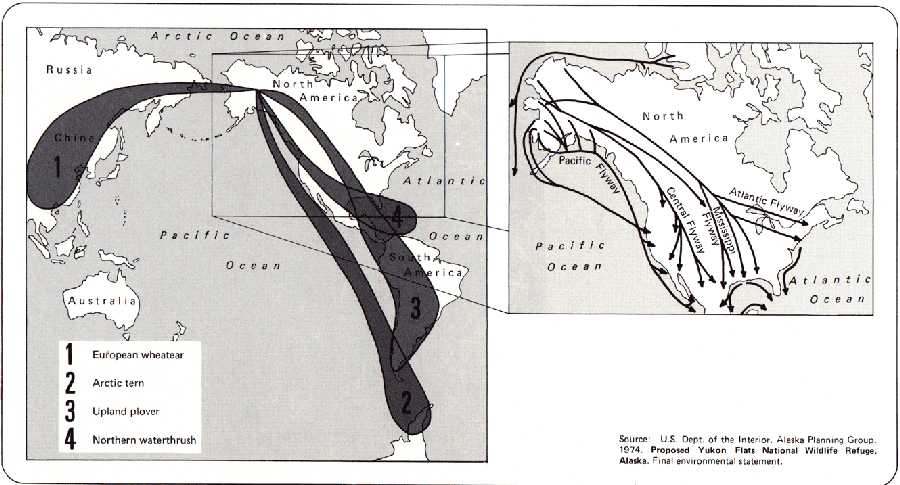

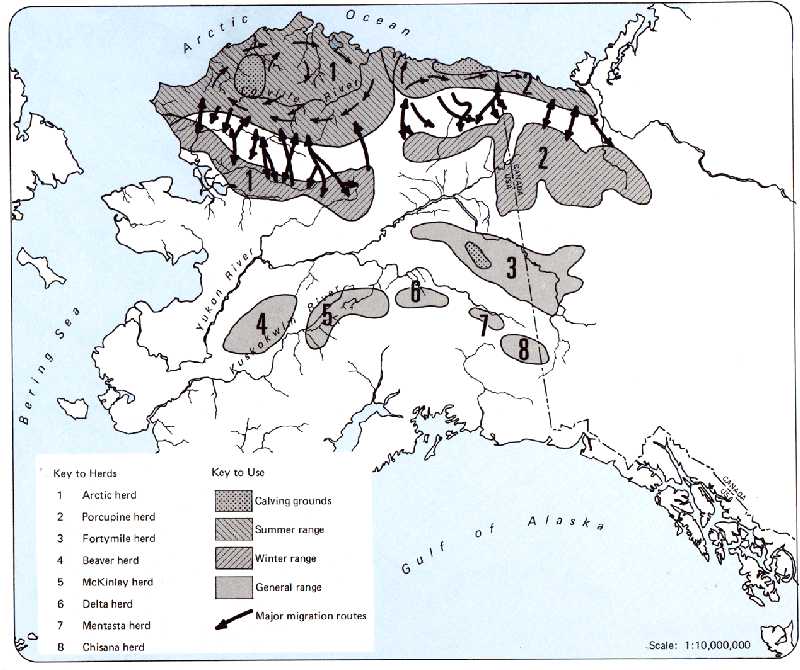

Several caribou herds range within the area (Figure 169). The Porcupine herd of about 150,000 animals migrates in a circular pattern in an area extending from the Koyukuk River in Alaska across the Canadian border into the headwaters of the Porcupine River and the Mackenzie River valley. The smaller Fortymile herd is about one-third the size of the Porcupine and generally ranges east of Livengood between the Yukon River and the Alaska Highway and eastward into Canada both winter and summer. The herd's calving grounds are in the White Mountains and the Tanana Hills. The small Delta, Chisana, Mentasta, and McKinley herds also range the southern portions of the Tanana River drainage. Dall sheep live in the alpine tundra of the Alaska Range, White Mountains, and the Brooks Range adjacent to the upper Yukon-Porcupine-Tanana River drainages. A few Fannin sheep, intermediate in color between the Dall sheep and the blackish Stone sheep of Canada, occur in the small extension of the Ogilvie Mountains that juts into Alaska just north of the Yukon River. Bison were introduced near Big Delta in 1928, and the herd has stabilized at between 200 and 300 animals. Some of this herd apparently winters near Healy Lake. Bison usually summer on the dry grass meadows on bars of the lower Delta and Gerstle Rivers. Winter range includes pastures that do not become wind packed, but they move to windswept alpine meadows east of the Delta River in late winter and spring.

Figure 169. Caribou Herds that Use the Yukon Region

Distribution of conspicuous species of mammals is shown in Figures 168, 170, 171, and 172. Other species are distributed throughout the region in suitable habitat as shown in the species lists for the plant communities.

|

Ermine are curious and tolerant of humans, sometimes even coming into buildings in search of voles or shelter. They occur in virtually all habitat types where small mammals and birds provide a food source.

|

|

These captive gray wolves show the same gregarious traits as their wild counterparts. Wolves occur throughout the region, even on the wet tundra. Alaska is one of the few remaining places where wolves can be seen regularly. |

|

High brush, either birch and willow in the lowlands or dwarf birch and other shrubs in the highlands, is an important part of moose habitat. This large mammal provides a basic food and fiber resource for human subsistence as well as recreation in the region and may be found in almost all habitats. It favors the high country in summer when the animals spread out over a large portion of the interior. In winter, they favor the river valleys where they can feed on new growth, concentrating particularly in willows or river bars and islands. |

Birds

Much of the Yukon Region provides excellent habitat for a diverse and abundant population of terrestrial birds. Millions of migratory birds transit the North American continent and north Pacific Ocean in spring to breed and nest on the lands drained by the Yukon River and its tributaries or on the rugged volcanic cliffs of St. Matthew, Pinnacle, and Hall Islands. Dozens of species of resident terrestrial birds remain in the region throughout the year.

The importance of the region's bird habitat has been recognized since the late 1950s when Bering Sea and Clarence Rhode National Wildlife Refuges were established to protect this valuable resource. In recent years, several other refuges have been proposed in the Yukon River delta as well as important bird staging areas adjacent to the Koyukuk River and the extensive Yukon River flats.

Along the shoreline of St. Matthew Island, precipitous basaltic cliffs that have been eroded by the sea provide nesting habitat for large colonies of such seabirds as cormorants, fulmars, gulls, murres, auklets, and puffins. Bird life on the tide flats and in the fresh- and brackish-water lakes has been poorly studied because ornithologists have visited the islands only a few times.

No raptors have been observed on St. Matthew, Hall, or Pinnacle Islands. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1968) noted that rough-legged hawks, gyrfalcons, peregrine falcons, and short-eared owls may occur there. The islands support such shorebirds as golden plovers, ruddy turnstones, wandering tattlers, rock and least sandpipers, and red and northern phalaropes. Hall and St. Matthew Islands are the only locations outside of the Pribilof Islands where Pribilof rock sandpipers are known to breed (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1973b).

Gray-crowned rosy finch, redpoll, Lapland (Alaska) longspur, and snow bunting are the most common passerine species of most of the Bering Sea islands. Insular populations have frequently evolved distinct races, so the Pribilof gray-crowned rosy finch (Leucosticte tephrocotis umbrina) is known to nest only in the Pribilofs and on Hall and St. Matthew Islands, and the McKay's snow bunting (Plectrophenax hyperboreus) nests only on St. Matthew Island. Other passerines found on St. Matthew include ravens, Arctic warblers, and savannah sparrows. Considerable ornithological research is needed before the relationship between avifauna on St. Matthew Island to other islands and to mainland Alaska and Siberia is clearly understood.

Numerous meandering streams cross the lowlands of the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta. Many of them are former channels of the Yukon River, and they offer a mixture of saline, brackish, and fresh habitats. Tidewater may extend more than 30 miles (48 km) up most coastal streams. The abundance of these streams, small thaw lakes, and marshy sedge meadows creates a coastal fringe of highly productive habitat for birds, even though its cool, cloudy, maritime climate suppresses total productivity. Inland from this coastal fringe, a superficially similar pond-stream-tundra habitat is somewhat less productive of some species on a unit area basis, but it covers a great expanse and is also an important part of the delta.

Raptors are uncommon on the delta, but the rough-legged hawk, marsh hawk, and peregrine falcon in the lowlands and gyrfalcon at higher elevations have been observed. Bald and golden eagles are rarely seen although they are common in adjacent areas. Snowy and short-eared owls also occur with the latter more common, particularly in years when rodents are numerous. The snowy owl is one of the few year-round residents. Both species of owls and rough-legged and marsh hawks are probably the only raptors that nest in the Yukon River delta.

Passerine birds are considerably less abundant on the delta than are shorebirds or waterfowl. The Lapland (Alaska) longspur and savannah sparrow are the most numerous of the smaller passerines. The longspur is found on heath tundra, while the savannah sparrow is generally observed adjacent to marsh areas and among patches of tall grass. Yellow wagtails, tree sparrows, and redpolls also are numerous, nesting in shrub patches or tall grass. Other small passerines recorded in the Yukon delta include McKay's and snow buntings, black-capped chickadees, robins, thrushes, sparrows, warblers, and several species of swallows. Most small birds leave the area by mid-September, although McKay's bunting commonly winters on the delta.

The gently sloping topography of the land bordering the Yukon River includes the lowland floodplains between the Innoko and Yukon Rivers and the lowland basins on the upper Innoko, Iditarod, Yentna, and Dishna Rivers. The numerous lakes and ponds of the region are primarily maintained by intermittent flooding of adjacent streams. Many aquatic birds live in these areas, and valleys farther in the Interior are nesting havens for passerine birds from all over North America and beyond. The lake-dotted alluvial "solar basins" of the central Yukon River and its tributaries support some of the most dense and diverse populations of nesting birds in Alaska. During winter, when these valleys fill with very cold air and become "cold sinks," few birds remain.

Raptors that commonly nest in the Koyukuk-Innoko area are red-tailed and rough-legged hawks, marsh hawks, ospreys, sparrow hawks, and short-eared and hawk owls. The goshawk and great-horned owl are common year-round residents in the valleys and gyrfalcons in the surrounding hills. Occasional nests of the golden eagle, peregrine falcon, and great gray owl have also been recorded, while sharp-shinned, Harlan's, Swainson's, and pigeon hawks, snowy owls, and bald eagles have also been observed (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1973a).

Lower and central Yukon River habitats are also important for shorebirds, particularly the common snipe. Other nesters or visitors include semipalmated, golden, and black-bellied plovers; Hudsonian godwits; greater yellowlegs; spotted and solitary sandpipers; and northern phalaropes. Less common are whimbrels, upland plovers, willets, Baird's and least sandpipers, dunlins, and red phalaropes.

The abundance of passerine birds in interior valleys and in the Koyukuk-Innoko area has been incompletely documented. However, common nesters include several species each of thrushes, warblers, blackbirds, finches, redpolls, sparrows, juncos, and crossbills. Occasional nesters are dippers, orange-crowned warblers, and northern three-toed woodpeckers. Water pipits, northern shrikes, snow buntings, Lapland (Alaska) longspurs, hoary redpolls, and belted kingfishers have also been recorded. A few such hardy passerine birds as ravens, jays, grosbeaks, crossbills, chickadees and, more rarely, yellow-shafted flickers and hairy and downy woodpeckers, remain in these latitudes all winter.

The upper Yukon River basin upstream from Rampart includes drainages from several large tributaries, including the Porcupine, Sheenjek, and Chandalar Rivers. It is best known for the highly productive bird habitats along the streams, lakes, and marshes and in the varied woodlands of the Yukon Flats.

Twenty species of raptors occur in the upper Yukon basin and 18 are known or suspected to breed there (Ritchie 1972). Bald eagles nest in small numbers along or near the Yukon River in the lowlands, while a few golden eagles nest on ledges and other areas associated with alpine tundra (U.S. Department of the Interior, Alaska Planning Group 1973a). Ospreys, goshawks, red-tailed hawks, and great horned owls are considerably more abundant than other large raptors and are widely distributed throughout forested habitats (U.S. Department of the Interior, Alaska Planning Group 1973b). America's largest falcon, the gyrfalcon, is known to occur in the highlands in the southern part of the area and may nest there.

The peregrine falcon is of particular importance because of its status as an endangered species and its abundance along the Yukon River. It may also nest along the lower reaches of the Charley River and on other tributaries of the Yukon. It appears to be diminishing in numbers, however. Eighteen to 20 pairs were counted along the Yukon River between Eagle and Circle in the early 1950s. Hickey (1969) reported 17 pairs along this same segment, and only 12 pairs were recorded in 1970.

Peregrines and their waterfowl prey are highly mobile and during spring, fall, and winter migrate to or through densely populated portions of the North American continent where the waterfowl consume significant quantities of pesticide residues with their food. These residues concentrate in their body tissues and then further concentrate in their predators. The metabolic toxins can reduce or even preclude reproductive success in birds. The long southward migration of the Arctic peregrine (Falco peregrinus anatum) make this species particularly vulnerable. Cade et al. (1968) found high pesticide levels in Arctic peregrines in the eastern Yukon River area.

Peregrine falcons nest on bluff faces too steep to support continuous vegetation or to provide access to the nest site by predators. A nest site may be used repeatedly, though it is common for a pair to utilize several sites over a period of years. Though the birds are very sensitive to human intrusion into the nesting area, it appears that river traffic on the Yukon does not lead to disruption of nesting activity.

Twenty-eight species of shorebirds including killdeer, plovers, surf birds, snipe, sandpipers, and phalaropes have also been recorded along river or lake shorelines in this area.

More than 60 species of passerine birds utilize the terrestrial habitats of the upper Yukon and adjacent lands. Common breeding birds are yellow-shafted flickers, Traill's flycatchers, cliff swallows, robins, water pipits, Bohemian waxwings, and several species of thrushes and sparrows. Some of the less common, but regular breeders are belted kingfishers, western wood peewees, horned larks, dippers, wheatears, northern shrikes, and chipping sparrows.

Despite long, cold winters, 14 species remain in the area year-round. Among these are several species of woodpeckers and chickadees, gray jays, black-billed magpies, common ravens, brown creepers, and common redpolls. Migratory or resident passerines which are relatively uncommon or rare are rufous hummingbirds, yellow-bellied flycatchers, barn swallows, starlings, pine siskins, and Oregon juncos (U.S. Department of the Interior, Alaska Planning Group 1973a).

Invertebrates

Of the million or more described species of animals in the world, approximately 95 percent are invertebrates. Bacteria, worms, and a host of other invertebrate species are responsible for the breakdown of natural organic matter. Invertebrates contribute greatly to the continuation of life by recycling nutrients important to other larger biota.

Terrestrial invertebrate populations in Alaska are perhaps as diverse as they are numerous, ranging from disease-causing bacteria in caribou to the annoying mosquito, which occurs in nearly every habitat of the Yukon Region. Much of the diversity of birds in summer depends on the abundance of insects, spiders, and mites for food. Saw flies are one of the most numerous insects and feed on willows. Other invertebrates, such as nematodes, are vital to the aeration and fertilization of soil. They digest and break down the accumulated plant detritus and recycle it into the soil where it becomes available for new plants.

Hoards of mosquitoes and midges live in moist and wet tundra environments, and they are essential to the seasonally abundant bird populations, particularly smaller passerine species. Peak mosquito populations usually occur from mid-June to early July.

In the lower Yukon area, the abundance of invertebrates in the mud along the edges of tundra ponds partially accounts for the tremendous numbers of shorebirds that nest in this habitat. Extensive stands of white spruce along the Porcupine, Coleen, Sheenjek, and Chandalar River drainages have long been infested by ips beetles (Ips sp.) which occur initially in flood- or fire-damaged trees from which they spread to healthy trees. The last recorded infestation occurred in the 1950s (Baker and Laurent 1974).

In alpine tundra environments a variety of insects is attracted to the scattered patches of snow that persist through summer. The arthropod fauna of isolated snow surfaces consist primarily of Dipteran and Hymenopteran species followed by Coleoptera and Hemiptera, the latter largely represented by aphids. These insects may drift onto the snow or are attracted toward the highly reflective snow surfaces (Edwards 1972) and provide food for such birds as water pipits, swallows, finches, ptarmigan, and snow bunting.

Plants on the tundra provide a favorable habitat for terrestrial fauna which feed on fungi and other plant tissues. These organisms seek shelter under lichens and mosses and among the roots of higher plants. Collembola feed on fungi and together with mites are universal and important agents in converting the vegetation to animal food. Collembola and mites are preyed upon by beetles, spiders, and other arthropods which in turn are preyed upon by vertebrate animals such as birds and small insectivorous mammals.

Insects are important food for freshwater fishes such as grayling and whitefish. Although many aquatic insects as larvae are the principal diet of many fish, adult winged insects commonly are eaten as they are blown or tumble into the water.

Parasites of big game and other mammals have gained increasing attention in recent years (Neiland 1965, 1970, 1975; Neiland et al. 1968). These organisms inhabit the internal organs and tissues of caribou, moose, and wolves as well as sled dogs and even man. They include many species of bacteria, protozoans, tapeworms, flukes, hookworms, and others. The botfly (Oedamagena tarandi) infests the hide of caribou, ruining it for any human use (Weber 1950). It and the blowfly are regularly associated with the carcasses of mammals.

The following lists indicate the species which are usually prominent in each of the vegetative types. No indication of the importance of interspecific relationships is intended. Each of these habitats may also be inhabitated by numerous other small mammals and birds.

Important Animals of

the Low Brush, Muskeg-Bog, High Brush,

Wet Tundra, and Moist Tundra Communities

Marine Mammals

Distribution of marine mammals in the north Bering Sea offshore of the Yukon Region is strongly influenced by sea ice. For several species of seals, ice takes the place of land and provides hauling grounds for resting and bearing young. Only one subspecies of harbor seal and the ribbon seal predominantly inhabit ice-free water, the former usually hauling out on land and the latter becoming pelagic as the ice pack retreats in spring. Other seals in the region are ice-loving, or "pagophilic." Of the marine mammals that occur in the region, Fay (1974) rated the walrus, all seals other than the one subspecies of harbor seal, and beluga and bowhead whales as maintaining regular contact with sea ice. He rated the killer, gray, humpback, fin, and minke whales and the harbor porpoise as having some contact with ice and the fur seal as having none.

Those in the first group usually stay at the edge of the drifting pack ice, an area of high basic productivity protected from heavy seas by the ice itself. Some of the ice-loving seals may not follow the ice edge south in autumn but remain north of the Yukon Region through the winter. Other individuals migrate south into and through the region in autumn with the advancing ice pack.

Bowhead whales, while they follow leads and can break ice as thick as nine inches (23 cm), can become entrapped in the pack if they venture too far into it. Beluga whales cannot break ice this thick and do not penetrate as far into the pack. Some bowheads remain in the ice north of the region through the winter, and few of those that do come south move close inshore in the region. Walrus also can become entrapped by solid ice and not be able to reach the water to feed (Fay in press). The general movement pattern of these animals is northward in spring as the ice edge retreats and southward in fall with the advance of the ice. Some whales, particularly the gray which winters in Baja California, migrate southward beyond the ice pack.

Walrus; harbor, ringed, ribbon, and bearded seals; and beluga, bowhead, gray, killer, fin, minke, and humpback whales are common in waters of the region. Several other whales, the Stellar sea lion, and northern fur seal also occur. Remains of polar bears have been found on St. Matthew Island, but this species has not been recorded there in recent time and does not occur elsewhere in the region.

Birds

The Yukon-Kuskokwim delta is one of the two major aquatic bird nesting habitats in Alaska. The delta is composed basically of two major types—a band of saline, meadowlike marsh of sedge (mainly Carex rariflora but including C. mackenziei), sometimes mixed with cinquefoil (Potentilla egedii) and grass (Poa eminens) that may extend inland as far as three to 15 miles (4.8 to 24 km) (Mickelson 1975) and a lake-studded plain about four feet (1.2 m) above mean high tide with a cover of wet or moist tundra that occupies the inland portion of the delta. The saline meadow marsh lies about a foot (30 cm) above mean high tide and is dotted with many small saline ponds and depressions that fill with water in spring but may go dry later in the season. It is also intersected by numerous tidal channels often bordered by a zone of coarse grass (Elymus sp.). Because of its low elevation, this zone is often inundated by sea water. The tundra zone is seldom covered with salt water because it is higher than the marsh. Lakes tend to be larger, and the tundra vegetation is less productive of most species of wildlife.

The saline marsh is by far the most productive habitat on the delta for nesting birds and is vital to many species. Here, black brant, cackling Canada and emperor geese, and common, spectacled, and Steller's eiders nest (Figure 173). More than 100 broods per square mile of the latter species may be produced in this habitat, and broods along the coastal fringe may even exceed one per acre. This habitat on the Clarence Rhode National Wildlife Refuge is the major nesting ground for this species in North America. Whistling swans and pintail ducks forage at the water's edge, and sandpipers, curlews, godwits, and red knots probe in the adjacent mud. Other species of birds, such as greater scaup, glaucous and glaucous-winged gulls, Arctic terns, parasitic and long-tailed jaegers, loons, and grebes are particularly common in these marshes. Pomarine jaegers also stop off here during their migrations. Jaegers are one of the most important predators of small birds and eggs, although their primary food is small mammals. Jaegers winter at sea from California to Chile and across the Pacific to New Zealand. More than five Arctic loon nests per square mile have been found on the Clarence Rhode Refuge. Lesser sandhill cranes nest on the tundra but bring their broods to these saline marshes after they have hatched.

|

|

|

The Arctic tern

is common in marshlands of the region. Its migration to the Antarctic

is among the longest for bird species nesting in Alaska.

|

|

The coastal marsh is the key to the productivity of the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta, which produces an average fall flight of about 2.3 million ducks, principally pintail, greater scaup, green-winged teal, oldsquaw, and eider ducks. This habitat unit is perhaps without equal for production of geese, providing nesting habitat for 50 percent of all black brant, 80 to 90 percent of all cackling and emperor geese, and essentially all of the white-fronted geese that migrate to the Pacific Flyway (Figure 165). In addition, the delta is used by migrant brant and Canada and snow geese, and the autumn population of these species is nearly 800,000. It is also a major nesting area for whistling swans, whose breeding population may exceed 40,000 (King and Lensink 1971 ). Probably no other area of similar size is so critical to so many species of waterfowl.

Most waterfowl produced on the delta winter in more southern regions of the Pacific Flyway, migrating either inland through interior Alaska and British Columbia or along the coast. Some populations may use both routes. Although all American wigeons appear to migrate along the inland route, pintails migrate both inland and along the coast. About half of the greater scaup produced on the delta moves along the coast to the Pacific Flyway, while the other half migrates southeasterly across Canada to the Great Lakes and eventually reaches the Atlantic coast. Canvasbacks probably follow the same routes. Some white-fronted geese appear to move nonstop for at least 2,500 miles (4,000 km) from the delta to interior valleys of California. Others travel inland over central Canada and the Midwest to Louisiana, Texas, and Mexico. Whistling swans from the delta winter in California, Nevada, and Utah. Most oldsquaws move only as far as the Bering Sea to mingle with ducks from the Soviet Union.

Shorebirds probably outnumber any other species group, and sandpipers, plovers, and phalaropes are among the most abundant. If no other birds occurred on the delta, this group alone would qualify the area as a unique habitat. The northern phalarope, western sandpiper, dunlin, and black turnstone are most numerous. Bar-tailed godwits are conspicuous because they are large and screech loudly whenever danger threatens their nesting territory. Whimbrels and bristle-thighed curlews migrate through the delta, and nonbreeders return to forage on coastal lowlands in early summer. The delta is the only known breeding ground of the bristle-thighed curlew, which winters from the Hawaiian and Marshall Islands south to Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, and the Marquesas Islands.

Golden plovers, bar-tailed godwits, bristle-thighed curlews, and ruddy turnstones migrate to islands throughout the South Pacific and may reach New Zealand or Australia. Red and northern phalaropes winter at sea in the same region and off the coast of South America, while other species, such as whimbrels, Hudsonian godwits, black-bellied plovers, sanderlings, dowitchers, and spotted, solitary, least, pectoral, western, and semi-palmated sandpipers, migrate along the Pacific coast or inland through North America to wintering areas in Mexico, Central America, and South America as far south as Cape Horn or Tierra del Fuego (Gabrielson and Lincoln 1959).

Freshwater

Aquatic environments of the Yukon Region are characterized by large alluvial basins that contain numerous marshes, lakes, slow-moving streams, and bogs. Such areas support various and abundant bird, mammal, and fish populations. Surrounding uplands usually contain deeper lakes, swifter streams, and few marshlands and support a different fish fauna and generally fewer mammals and birds.

Invertebrates and Fish

Zooplankton of the freshwater lakes and streams in this region have never been studied in detail, and little recorded information is available concerning their abundance and distribution. Hooper (1947) reported the presence of two species of rotifers but no cladocera or copepods from the Yukon River at Galena. Nauman and Kernodle (1974) reported small numbers of copepods, cladocera, and ostracods from the streams and lakes along the route of the trans-Alaska pipeline where it crosses the Yukon River valley.

Benthic macroinvertebrates are common in the lakes and streams of this region. Nauman and Kernodle (1974) reported that midges, stoneflies, caddisflies, mayflies, blackflies, and freshwater mites are common in streams flowing south from the Brooks Range into the Yukon River along the trans-Alaska pipeline route. In lakes of this region a variety of clams, snails, aquatic earthworms, and flatworms are common. In rivers flowing northward from the Alaska Range into the Yukon River, Nauman and Kernodle (1974) found midges, caddisflies, and mayflies as the predominant benthic invertebrates. The major contrast between these tributaries and those entering the Yukon from the north was that stoneflies were much less abundant in the tributaries entering from the south than in those entering from the north. Morrow (1971b) found, in studies on the Chatanika River, that mayflies were the dominant benthic invertebrates in the early part of the summer, whereas midges became dominant as the summer progressed. Caddisflies and stoneflies were present in the lower portions of this drainage. In the headwaters stoneflies dominated, and the number of mayflies decreased; midge larvae were scarce, and blackfly larvae became extremely abundant.

The most widely distributed fish in the Yukon River basin are several species of whitefish, Arctic grayling, slimy sculpin, burbot, Arctic lamprey, longnose sucker, northern pike, and three species of Pacific salmon—chum, king, and silver. Grayling may occur in winter in larger rivers such as the Tanana and usually spawn in mid-June in smaller tributaries (Wojcik 1955). Large numbers of anadromous lamprey on spawning migrations may be conspicuous in some years. In addition, lake trout and lake chum are restricted to the headwater portions of the Yukon River basin including the Koyukuk, Chandalar, Sheenjek, and Tanana River drainages. Several species are restricted to the lower reaches of the Yukon River and its delta area, including the Bering cisco, ninespine stickleback, blackfish, Arctic char, and pink and red salmon.

Several distinct populations or stocks of inconnu (sheefish) inhabit the Yukon River basin. Fish which inhabit the lower Yukon River and delta spawn in upstream tributaries of the Koyukuk River. Another stock inhabits the Chatanika River-Minto Flats area. A third group, whose spawning area has not been discovered, occurs in the Porcupine River drainage. Some overlap of range between these groups may occur in the middle Yukon River.

A few red salmon inhabit the lower Yukon River drainage. Pink salmon spawn in considerable numbers in the Andreafsky River drainage in the lower Yukon River. Silver salmon are found throughout the Yukon River drainage, although their late spawning run has negated attempts to define their distribution and abundance in detail. King salmon inhabit the entire river with significant spawning populations occurring as far upstream as the Yukon Territory. Chum salmon in the Yukon River undertake one of the longest spawning runs known for their species and enter the river twice each year—a summer run and a fall run. In years of abundance the total number of chum salmon on the Yukon River may number several million and at times, such as in 1975, approach 10 million fish. Major spawning rivers include the Andreafsky and Anvik Rivers on the lower Yukon, the Koyukuk in the middle Yukon, and various tributaries of the Porcupine and Tanana Rivers in the upper Yukon. Chum salmon migrate upstream beyond Alaska into the Yukon Territory in both the Porcupine and Yukon River drainages. Distribution of salmon-spawning areas in the Yukon River drainage is not completely understood due to the sparse habitation of most of this region, the late arrival of certain runs in upstream areas each season, and the turbidity of Yukon River drainage waters which prevents visual counts.

Yukon Delta—The delta area has a myriad of lakes with a few streams that support various species of whitefish, northern pike, and some salmon. King, chum, and silver salmon migrate up the Yukon to reach their distant spawning grounds. The Andreafsky River drainage is utilized by king, chum, pink, and silver salmon. Several short coastal streams are also used by pink, chum, and king salmon. Other species of fish in the area are inconnu (sheefish), Arctic char, Arctic grayling, and burbot.

Yukon River—Along most of the main Yukon River there are comparatively few small streams and a limited number of lakes. The Yukon River is used by king, silver, and chum salmon that migrate upstream to distant spawning grounds. Important salmon spawning tributaries include the Anvik, Innoko, Nulato, Nowitna, Tozitna, Hodzana, Chandalar, Kandik, Nation, and Charley Rivers and Beaver Creek. The Yukon Flats contain a number of lakes and provide excellent habitat for whitefish and northern pike. Grayling, northern pike, and whitefish are found throughout the main drainage of the Yukon River.

Koyukuk River—Important king and chum salmon spawning and rearing streams include the Gisasa, Kateel, Huslia, Hogatza, Indian, Kanuti, Alatna, Wild, the lower Koyukuk, the south and middle forks of the Koyukuk River, and Henshaw Creek. Inconnu spawn in the main Koyukuk River near Hughes and in the Alatna River near the mouth of Siruk Creek. Northern pike and Arctic grayling are found throughout the area. Wild, Helpmejack, Iniakuk, and probably other lakes support lake trout.

Tanana River—Chum salmon spawn in a number of tributaries of the Tanana River. Silver salmon spawn and rear in the Chatanika and Salcha Rivers and Clearwater Creek. King salmon also spawn and rear in these streams as well as the Goodpaster, Delta, and Chena Rivers. Arctic grayling, whitefish, and northern pike are present throughout the area. Lake trout, inconnu, and cisco are scattered in various drainages.

Porcupine River—King, chum, and some silver salmon spawn and king and silver rear in the Sheenjek, Black, and Porcupine Rivers. Arctic grayling, northern pike, and whitefish are found throughout this drainage.

Birds

The Yukon-Kuskokwim delta and the Yukon Flats are the largest and most productive aquatic bird habitats in the region. Water—lakes, rivers, sloughs, and small streams—is perhaps the most important habitat factor. A million or more ponds are scattered over the warm valley habitats of the Yukon, Tanana, and Koyukuk Rivers and the tundra of the Yukon delta. Here, millions of waterfowl and shorebirds nest and rear their young.

The Bering Sea islands of Hall, Pinnacle, and St. Matthew have been incompletely surveyed for freshwater bird habitats, but they are known to support several species of sandpipers and phalaropes as well as golden plovers, dunlins, and wandering tattlers. Other water birds observed on and near St. Matthew Island include whistling swans, mallards, pintails, green-winged teal, oldsquaws, harlequins, king eiders, red-throated loons, and others. Steller's and spectacled eiders may occur there during migration. Lesser sandhill cranes also occur on Hall and St. Matthew Islands and probably nest there (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1973b).

Freshwater bird habitats on the Yukon delta, although not as productive on a unit-area basis as the coastal saline marshes, are an important habitat for many species because they are so extensive. Large populations of shore and water birds, including gulls, cranes, loons, grebes, plovers, snipe, and sandpipers, nest there.

Loons, predominantly Arctic but also red-throated and common, occur throughout the area. Red-necked and horned grebes are relatively uncommon along the coast but become more numerous inland. Lesser sandhill cranes are abundant during summer throughout their tundra nesting grounds.

Large breeding colonies of gulls are not often found on the delta. The large glaucous gulls nest in small colonies or singly in coastal lowlands, while the smaller and less abundant glaucous-winged gulls nest principally in cliff habitats away from the delta. Both gulls prey extensively on waterfowl eggs and young, although fish and invertebrates constitute their primary foods. Mew, Sabine's, and Bonaparte's gulls are also common throughout the area during nesting season. Their migrations take them to Cape Horn and Antarctica. The Aleutian tern (Sterna aleutica) nests primarily in the Aleutian Islands but is occasionally observed on the delta.

Ducks, more than 30 percent of which are greater scaup, oldsquaw, and pintail, are more numerous than geese. Other species in the area are common scoters, green-winged teal, mallards, and American wigeons.

The quality of inland habitats depends more on the number of lakes and ponds than on the total water area. Large lakes are important to molting birds in summer and as staging areas during fall migration. Other important staging areas are located along sandbars and islands of larger river systems.

The central Yukon River region contains several lake-dotted alluvial basins which support excellent summer habitat for aquatic birds. Areas such as the Koyukuk-Innoko unit support glaucous, glaucous-winged, mew, Bonaparte's, and a few herring gulls (Larus argentatus) as well as Arctic terns and parasitic and long-tailed jaegers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1973a). Several species of shorebirds, particularly the common snipe, also inhabit the area. Several species of plover and sandpiper are common nesters or visitors, while whimbrels, godwits, lesser yellowlegs, dunlins, sanderlings, and red phalaropes are less common.

More than a million ducks and 450,000 geese migrate out of the Koyukuk-Innoko area in autumn. On the average 180,000 white-fronted geese nest there annually, along with 175,000 pintails and 154,000 scaup. American wigeon, mallards, green-winged teal, and scoters number more than 35,000.

Swans, geese, and ducks are the major water birds in the central Yukon River region. The northwestern limit of trumpeter swans probably extends to the Koyukuk and Nowitna areas, and 330 and 120 swans nest in these two units, respectively. The remote nesting sites of trumpeters are generally safe from human intrusion most of the summer. Their numbers have recently risen in the area, and increased protection could result in the Koyukuk valley becoming an important area for this scarce species, only recently removed from the endangered list. These birds winter from southeast Alaska to the Columbia River along the Pacific coast (U.S. Department of the Interior, Alaska Planning Group 1973b). The lnnoko River basin is on the fringe of the favored nesting habitat of the whistling swan and about 100 pairs nest there.

White-fronted geese commonly nest on all units of the Koyukuk-Innoko area. Most migrate to Canada, primarily Saskatchewan, and the remainder travel to the Pacific Flyway, the Central Flyway, and to Mexico. Essentially all white-fronted geese from the Koyukuk move south along the Central Flyway. Lesser Canada geese also nest throughout the Koyukuk-Innoko area. Most winter in Washington and Oregon, but a few migrate to British Columbia and California.

The pintail is perhaps the most abundant dabbling duck of the Innoko basin, although American wigeon, mallards, green-winged teal, and northern shovelers also occur in substantial numbers. Most of these birds migrate down the Pacific Flyway—the mallard mainly to Washington and the others mainly to California. Scaup are the most abundant diving ducks nesting in the central Yukon, and about half migrate to the Mississippi Flyway. Most of the few greater scaup nesting in the area migrate to the Atlantic Flyway. The canvasback, a species not well adapted to the changes occurring on much of its range, nests in small numbers in the area (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1973a).

Other water birds commonly nesting in the Koyukuk-Innoko area include common, Arctic, and red-throated loons and horned and red-necked grebes—the latter is probably the most abundant. Sandhill cranes nest by the thousands throughout the area.

The 10,800-square-mile (27,972 km2) Yukon Flats is probably the largest and most productive warm basin in arctic or Yukon Alaska and is one of the two most important habitats in the region. Water is the dominant feature; this habitat contains thousands of lakes and ponds averaging about 20 acres (8.1 ha) in size and is traversed by more than 25,000 miles (40,000 km) of streams.

The most productive ponds are usually those that are at some distance from active stream channels, are flooded infrequently, and do not drain off into streams. Drainage into channels reduces the nutrients in the ponds, and they are usually less productive. Flooding of the river systems inundates lakes, ponds, and sloughs on the flats and provides their water supply. Prolonged periods of receding water levels increase the concentration of nutrients and productivity of these "closed basins" (King and Lensink 1971).

Lakes and ponds in burn areas are generally more fertile and productive than those in mature or climax forests. Fire darkens the soil so it absorbs more sunlight, warms, and releases more nitrogen from decaying vegetation, most of it probably into the air, but some leaches into nearby water (Lutz 1956; Heinselman 1971). Differences in plant cover and interspersion of various types caused by differences in soils, drainage, erosion by streams, permafrost, and forest fires contribute to the productivity of the area for various forms of wildlife.

Most lakes are shallow or have extensive shallow areas which support a luxuriant growth of aquatic plants. Migratory bird use is related to both type and density of aquatic and shoreline vegetation. Birds prefer lakes where submerged pondweeds, water milfoil, and coontail are abundant and where shoreline vegetation is broken or only moderately dense.

The greatest importance of the Yukon Flats to aquatic birds is for nesting and rearing their young. They are able to reproduce there even in years when drought eliminates many breeding areas to the south. Although some prairie and parkland habitats of Canada and the more northcentral United States are more productive in good years, they are unproductive during drought. Ducks that normally nest in the prairies are known to nest in the flats during such periods, and other species probably do also (Hansen and McKnight 1964).

Large productive lakes are important molting habitats for ducks in late summer, not only for those that nest or are raised on the flats, but also for molting birds from distant areas. Southward migrants concentrating in this fertile area comprise a significant portion of the population in fall. Both ducks and geese are found in great numbers on many lakes and on islands and bars of the Yukon River where migrating geese graze extensively on horsetails growing on dewatered mud flats. Many thousands of snow geese pass through during migration, and occasional small flocks of black brant have been observed in spring.

Waterfowl arrive shortly before breakup in April or May when the first snowmelt forms small ponds. These ponds become ice-free relatively early, and some of the ducks and geese found there in the spring move on farther north and west.

Numerous species of birds nest on the Yukon Flats, but waterfowl, especially ducks and geese, are the most conspicuous. An average of about 2.1 million ducks and geese leave the Yukon Flats in fall, and ducks raised there are known to migrate to 43 states in all flyways (King and Lensink 1971). Ducks are most abundant in shallow, fertile lakes at low elevations. American wigeon and lesser scaup predominate, followed by pintail, green-winged teal, white-winged scoters, and northern shovelers. About 50,000 canvasbacks—10 to 15 percent of the average North American population—nest on the flats. About 8,000 Canada geese nest near the larger lakes and a smaller number of white-fronted geese nest near the perimeter of the area, usually on the banks of small wooded streams.

About 10,000 sandhill cranes, 15,000 Arctic loons, and smaller numbers of common and red-throated loons nest on the Yukon Flats, usually on large, deep lakes. Horned and red-necked grebes, like ducks, are most abundant in shallow, fertile lakes. Grebes are shy and escape observation by hiding in vegetation or by prolonged submergence. This makes estimates of their numbers impossible, but they occur on nearly every lake or pond, and their numbers may exceed 100,000. A few trumpeter swans nest in the larger lakes.

Few species of seabirds occur on the flats or other upper Yukon areas, but herring, mew and Bonaparte's gulls, Arctic terns, and long-tailed jaegers occur there as well as 28 species of shorebirds, such as golden plovers, spotted sandpipers, dunlins, and several species of yellowlegs and phalaropes. The upper Yukon-Tanana-Porcupine area has many other smaller units of habitat, usually in broad stream valleys or margins of lakes which support water birds of various species.

The Minto Flats are smaller than the Yukon Flats, but in good years they are even more productive. However, this unit is subject to frequent, severe spring flooding which may eliminate most nesting activity for the season and limit the area's average productivity.

The lakes and marshes near Tetlin are also well known as habitat for aquatic birds, and the large lakes are used heavily by molting ducks in summer. Species using these areas are similar to those using the Yukon Flats.

Mammals

Several species of mammals inhabit freshwater habitats of the Yukon Region for all or part of their life cycles.

Muskrat, mink, river otter, and beaver live throughout the region. Muskrat thrive in water that sustains succulent vegetation and are most common on such productive areas as the Yukon Flats. Both mink and river otter are carnivorous, so their abundance depends on the availability of prey. Mink on the Yukon delta are exceptionally large and noted for their fur. Both species may occur in flowing streams or still water. Beavers occur wherever there are slow-flowing or still waters and sufficient food. They feed on the inner bark of birch, aspen, cottonwood, and willow, and although they can subsist on the small varieties of these trees, they do not occur commonly on tundra.

Moose are not truly aquatic, but in summer they may spend much of their time in lakes, relatively free from fly and mosquito attacks. They feed on tuberous lily roots on lake bottoms.

|

Important Animals of the Freshwater Environment |

|||

|

Invertebrates |

|||

|

Bacteria |

Schizomycetes (Phylum) |

Mallard |

Anas platyrhynchos |

|

Rotifers |

Rotifera (Class) |

Pintail |

A. acuta |

|

Flagellates |

Mastigophora (Phylum) |

American wigeon |

A. americana |

|

Ciliates |

Ciliophora (Phylum) |

Northern shoveler |

A. clypeata |

|

Flatworms |

Turbellaria (Class) |

American green-winged teal |

A. crecca |

|

Aquatic worms |

Oligochaeta (Class) |

Canvasback |

Aythya valisineria |

|

Crustaceans |

Copepoda (Class) |

Greater scaup |

A. marila |

|

Cladocera (Order) |

Lesser scaup |

A. affinis |

|

|

Anostraca (Order) |

Common goldeneye |

Bucephala clangula |

|

|

Notostraca (Order) |

Bufflehead |

B. albeola |

|

|

Ostracoda (Class) |

Harlequin duck |

Histrionicus histrionicus |

|

|

Midge larvae |

Chironomidae (Family) |

Spectacled eider |

Somateria fischeri |

|

Mosquito larvae |

Culicidae (Family) |

Steller's eider |

Polysticta stelleri |

|

Blackfly larvae |

Simulidae (Family) |

Oldsquaw |

Clangula hyemalis |

|

Dragonfly larvae |

Odonata (Order) |

Black scoter |

Melanitta nigra |

|

Stonefly larvae |

Plecoptera (Order) |

White-winged scoter |

M. deglandi |

|

Mayfly larvae |

Ephemeroptera (Order) |

Surf scoter |

M. perspicillata |

|

Caddisfly larvae |

Trichoptera (Order) |

Lesser sandhill crane |

Grus canadensis |

|

Bettles |

Coleoptera (Order) |

Semipalmated plover |

Charadrius semipalmatus |

|

Mites |

Acarina (Order) |

Whimbrel |

Numenius phaeopus |

|

Clams |

Pelecypoda (Class) |

Bristle-thighed curlew |

N. tahitiensis |

|

Snails |

Gastropoda (Class) |

Bar-tailed godwit |

Limosa lapponica |

|

Black turnstone |

Arenaria melanocephala |

||

|

Fish |

Rock sandpiper |

Calidris ptilocnemis |

|

|

Chum (dog) salmon |

Oncorhynchus keta |

Dunlin |

C. alpina |

|

Pink (humpback) salmon |

O. gorbuscha |

Western sandpiper |

C. mauri |

|

King (chinook) salmon |

O. tshawytscha |

Sanderling |

C. alba |

|

Silver (coho) salmon |

O. kisutch |

Lesser yellowlegs |

Tringa flavipes |

|

Red (sockeye) salmon |

O. nerka |

Red phalarope |

Phalaropus fulicularius |

|

Arctic char |

Salvelinus alpinus |

Northern phalarope |

Lobipes lobatus |

|

Lake trout |

S. namaycush |

Common snipe |

Capella gallinago |

|

Arctic grayling |

Thymallus arcticus |

Parasitic jaeger |

Stercorarius parasiticus |

|

Whitefish and cisco |

Coregonus spp. |

Pomarine jaeger |

S. pomarinus |

|

Inconnu |

Stenodus leucichthys |

Long-tailed jaeger |

S. longicaudus |

|

Northern pike |

Esox lucius |

Glaucous gull |

Larus hyperboreus |

|

Sculpin |

Cottidae (Family) |

Glaucous-winged gull |

L. glaucescens |

|

Burbot |

Lota Iota |

Mew gull |

L. canus |

|

Ninespine stickleback |

Pungitius pungitius |

Bonaparte's gull |

L. philadelphia |

|

Longnose sucker |

Catostomus catostomus |

Sabine's gull |

Xema sabini |

|

Lake chub |

Couesius plumbeus |

Arctic tern |

Sterna paradisaea |

|

Alaska blackfish |

Dallia pectoralis |

Dipper |

Cinclus mexicanus |

|

Birds |

Mammals |

||

|

Common loon |

Gavia immer |

Beaver |

Castor canadensis |

|

Arctic loon |

G. arctica |

Muskrat |

Ondatra zibethica |

|

Red-throated loon |

G. stellata |

Mink |

Mustela vison |

|

Red-necked grebe |

Podiceps grisegena |

River otter |

Lutra canadensis |

|

Horned grebe |

P. auritus |

Moose |

AIces alces |

|

Whistling swan |

Olor columbianus |

||

|

Trumpeter swan |

O. buccinator |

||

|

Canada goose |

Branta canadensis |

||

|

White-fronted goose |

Anser albifrons |

||

|

Snow goose |

Chen caerulescens |

||

Aquatic Animals

Village life in the Yukon Region still depends heavily on hunting and fishing along the many streams and lakes.